Fuel Cells

Fuel cells are the most energy efficient devices for extracting power from fuels. Capable of running on a variety of fuels, including hydrogen, natural gas, and biogas, fuel cells can provide clean power for applications ranging from less than a watt to multiple megawatts.

Our transportation—including personal vehicles, trucks, buses, marine vessels, and other specialty vehicles such as lift trucks and ground support equipment, as well as auxiliary power units for traditional transportation technologies—can be powered by fuel cells. They can play a particularly important role in the future by enabling replacement of the petroleum we currently use in our cars and trucks with cleaner, lower-emission fuels like hydrogen or natural gas.

Stationary fuel cells can be used for backup power, power for remote locations, distributed power generation, and cogeneration (in which excess heat released during electricity generation is used for other applications). They can take advantage of inexpensive natural gas and low-carbon fuels like biogas, enabling significant efficiency improvement and greenhouse gas reduction when compared to combustion-based power generators. Fuel cells can power almost any portable application that typically uses batteries, from hand-held devices to portable generators.

Why Fuel Cells?

Fuel cells directly convert the chemical energy in hydrogen to electricity, with pure water and potentially useful heat as the only byproducts. Hydrogen-powered fuel cells are not only pollution-free, but they can also have more than two times the efficiency of traditional combustion technologies.

A conventional combustion-based power plant typically generates electricity at efficiencies of 33 to 35%, while fuel cell systems can generate electricity at efficiencies up to 60% (and even higher with cogeneration).

The gasoline engine in today’s typical car is less than 20% efficient in converting the chemical energy in gasoline into power that moves the vehicle, under normal driving conditions. Fuel cell vehicles, which use electric motors, are much more energy efficient. The fuel cell system can use 60% of the fuel’s energy—corresponding to more than a 50% reduction in fuel consumption compared to a conventional vehicle with a gasoline internal combustion engine. When using hydrogen produced from natural gas, fuel cell vehicles are expected to have well-to-wheels greenhouse gas emissions less than half that of current gasoline-powered vehicles.

In addition, fuel cells operate quietly, have fewer moving parts, and are well suited to a variety of applications.

Excess power produced by intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind can be stored in the form of hydrogen, and either fed back into the power grid when needed or used to power fuel cell electric vehicles. In this way, fuel cells could play an important role in aiding the widespread deployment of clean renewable power sources.

How Do Fuel Cells Work?

A single fuel cell consists of an electrolyte sandwiched between two electrodes, an anode and a cathode. Bipolar plates on either side of the cell help distribute gases and serve as current collectors. In a Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) fuel cell, which is widely regarded as the most promising for light-duty transportation, hydrogen gas flows through channels to the anode, where a catalyst causes the hydrogen molecules to separate into protons and electrons. The membrane allows only the protons to pass through it. While the protons are conducted through the membrane to the other side of the cell, the stream of negatively-charged electrons follows an external circuit to the cathode. This flow of electrons is electricity that can be used to do work, such as power an electric motor.

On the other side of the cell, air flows through channels to the cathode. When the electrons return from doing work, they react with oxygen in the air and the protons (which have moved through the membrane) at the cathode to form water. This union is an exothermic reaction, generating heat that can be used outside the fuel cell.

The power produced by a fuel cell depends on several factors, including the fuel cell type, size, temperature at which it operates, and pressure at which gases are supplied. A single fuel cell produces roughly 0.5 to 1.0 volt, barely enough voltage for even the smallest applications. To increase the voltage, individual fuel cells are combined in series to form a stack. (The term “fuel cell” is often used to refer to the entire stack, as well as to the individual cell.) Depending on the application, a fuel cell stack may contain only a few or as many as hundreds of individual cells layered together. This “scalability” makes fuel cells ideal for a wide variety of applications, from vehicles (50-125 kW) to laptop computers (20-50 W), homes (1-5 kW), and central power generation (1-200 MW or more).

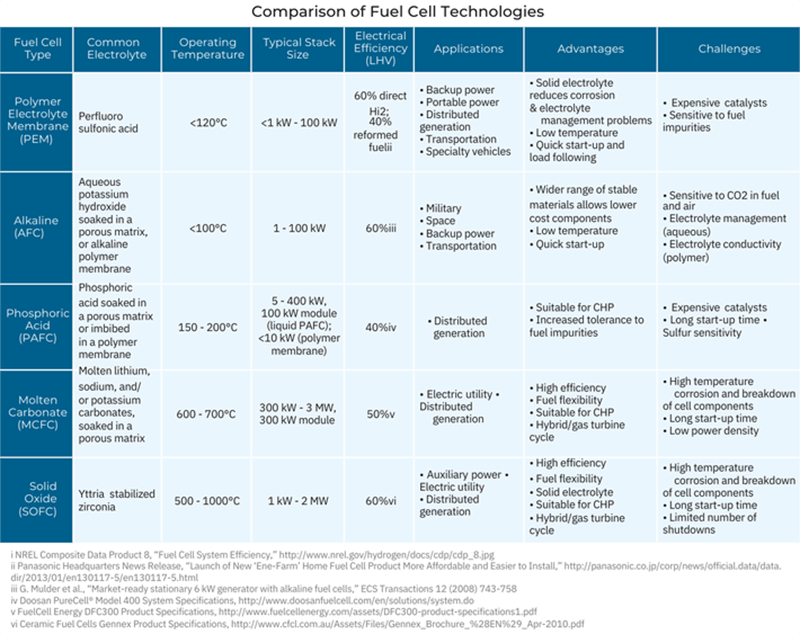

Comparison of Fuel Cell Technologies

In general, all fuel cells have the same basic configuration — an electrolyte and two electrodes. But there are different types of fuel cells, classified primarily by the kind of electrolyte used. The electrolyte determines the kind of chemical reactions that take place in the fuel cell, the temperature range of operation, and other factors that determine its most suitable applications.

Challenges and Research Directions

Reducing cost and improving durability are the two most significant challenges to fuel cell commercialization. Fuel cell systems must be cost-competitive with, and perform as well or better than, traditional power technologies over the life of the system. Ongoing research is focused on identifying and developing new materials that will reduce the cost and extend the life of fuel cell stack components including membranes, catalysts, bipolar plates, and membrane-electrode assemblies. Low-cost, high-volume manufacturing processes will also help to make fuel cell systems cost competitive with traditional technologies.

For More Information

More information on the Fuel Cell Technologies Office is available at http:// www.hydrogenandfuelcells.energy.gov.